No surprises here – it’s mostly architecture and urbanism books. But wait! There’s a novel and a biography in there too.

If you want to jump ahead, just click a link. This installment covers Walkable City by Jeff Speck, Strong Towns by Charles Marohn, Confessions of a Recovering Engineer by Charles Marohn, The Nickel Boys by Colson Whitehead, A Song for Nagasaki by Paul Glynn. Stick around to the end for a movie recommendation!

Would you shut up about urbanism already?

No.

Walkable City (10th Anniversary Edition)

by Jeff Speck

If you can read one contemporary book about cities and what makes them work, this should be it (if you can read an older book too, go with The Death and Life of Great American Cities by Jane Jacobs). Jeff Speck analyzes the problems of our auto-centric cities and ‘burbs, and provides 10 steps to make a place walkable. No, it’s not as simple as building sidewalks, as anyone who has walked a quarter mile each way down a suburban stroad to get to a crosswalk knows.

If you can read one contemporary book about cities and what makes them work, this should be it (if you can read an older book too, go with The Death and Life of Great American Cities by Jane Jacobs). Jeff Speck analyzes the problems of our auto-centric cities and ‘burbs, and provides 10 steps to make a place walkable. No, it’s not as simple as building sidewalks, as anyone who has walked a quarter mile each way down a suburban stroad to get to a crosswalk knows.

What I love about this book is that it makes such a clear case for why walkability is the deciding factor that determines whether a place is alive or dead, and then provides insights on how to get there. It’s not just an invective against the suburbs (although it is that); it’s a way forward.

The 10th anniversary edition, published in 2022, is not a simple re-release. It contains about 100 pages of new content, going over the things that happened during COVID, the housing crisis, and many other topics of immediate importance to anyone looking to improve their city / town / suburb now. Buy it (not from Amazon) and read it. If you don’t like it, I will buy it from you for whatever you paid. As long as you bought it from a local bookstore.

Strong Towns: A Bottom-Up Revolution to Rebuild American Prosperity

by Charles Marohn

Over the last several months I’ve been getting to know a great organization called Strong Towns. They have three podcasts, all of which are worth checking out. The founder, Chuck Marohn, wrote two books, both of which I read recently. In the first book, Marohn makes a (fairly conservative) economic case for traditional urban development. Cities, he argues, should be built and “intensified” incrementally, as growth makes the next level of growth beneficial. People should be encouraged to make thousands of “small bets” in terms of development, small enough that if it doesn’t work they can try again. Start with a food truck. If it’s a success, maybe rent a small space in an inexpensive building. Line out the door? Maybe it’s time to expand. Cooks playing sudoku on their phones because they have nothing to do? Back to the drawing board. Instead of this, the current paradigm involves building whole developments to a finished state – this is a big bet, and when one of them doesn’t work out, it leaves a huge amount of building and infrastructure, creates a financial drain on the community, and makes the place look and feel uninviting, which makes others less inclined to open their businesses there. If you want to see what this looks like, come to Portland and visit one of our Walmarts. Walmart only pulled out of Portland a few months ago, and their buildings and acres of parking lot already make you feel like you accidentally stepped into The Walking Dead.

Over the last several months I’ve been getting to know a great organization called Strong Towns. They have three podcasts, all of which are worth checking out. The founder, Chuck Marohn, wrote two books, both of which I read recently. In the first book, Marohn makes a (fairly conservative) economic case for traditional urban development. Cities, he argues, should be built and “intensified” incrementally, as growth makes the next level of growth beneficial. People should be encouraged to make thousands of “small bets” in terms of development, small enough that if it doesn’t work they can try again. Start with a food truck. If it’s a success, maybe rent a small space in an inexpensive building. Line out the door? Maybe it’s time to expand. Cooks playing sudoku on their phones because they have nothing to do? Back to the drawing board. Instead of this, the current paradigm involves building whole developments to a finished state – this is a big bet, and when one of them doesn’t work out, it leaves a huge amount of building and infrastructure, creates a financial drain on the community, and makes the place look and feel uninviting, which makes others less inclined to open their businesses there. If you want to see what this looks like, come to Portland and visit one of our Walmarts. Walmart only pulled out of Portland a few months ago, and their buildings and acres of parking lot already make you feel like you accidentally stepped into The Walking Dead.

Confessions of a Recovering Engineer

by Charles Marohn

This is another book by the founder of Strong Towns. I actually liked it much more than the first one. That’s partly because I’m an ex-engineer (not a civil engineer like Marohn, though) and I’m sympathetic to many of his critiques of the profession.

This is another book by the founder of Strong Towns. I actually liked it much more than the first one. That’s partly because I’m an ex-engineer (not a civil engineer like Marohn, though) and I’m sympathetic to many of his critiques of the profession.

In Confessions, Marohn reflects on his own time working as a civil engineer and designing roads, intersections, and suburban developments that he now believes to be deadly. He makes a clear and convincing case that almost the entire road engineering profession is stuck in a way of building that is to blame for the absurdly high rate of traffic deaths in the United States.

A key insight from the book: after mostly falling since the late ’60s, per capita car crash fatalities rose 7.1% in 2020, and another 10.5% in 2021. This despite the fact that Americans drove far fewer miles during COVID-related lockdowns. In 2021 , 42,939 Americans died because of car crashes. The official explanation for the sudden spike: Americans felt angsty and cooped up because of lockdowns and suddenly decided to do a lot more drunken joy-riding without our seatbelts on. Laughable, but good enough to absolve anyone who has a vested interest in not knowing the real reason (as Upton Sinclair put it, “It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends upon his not understanding it.”). Marohn provides a much more plausible explanation. The roads were empty. Where we used to sit in traffic, we could finally drive the speeds that felt right for the roads. As we all know, those speeds are usually 10-20 mph above the posted speed limits. Add to this the fact that traffic enforcement (at least in Portland, but I think this was true many other places) fell right off a cliff as police budgets were tightened. Why did Americans suddenly start to die on the roads at much greater rates? Because speed – especially when combined with the randomness of pedestrians, turning cars, etc. – is deadly.

Marohn provides a lot of suggestions for how to stop killing each other with cars. And no, “follow the posted speed limit” is not really one of them. Because our roads (well, our “stroads,” a term Marohn coined. Click the link to read a description I wrote below) are designed to be driven fast. Instead, we need to decide whether a given stroad will be a street or a road – whether its purpose will be people, or whether it will be cars, and cars only. Either is fine, but it cannot be both. Or it can, if we’re okay with killing 42,939 Americans a year. Which we shouldn’t be. To make a stroad into a street, traffic has to be slowed to speeds that are unlikely to kill pedestrians (read: 15 mph max). The best way to do this is by narrowing travel lanes, increasing the number of stops with stop signs, and making the road confusing. All that extra space can be use for sidewalks, street cafes, dedicated bike lanes, and parallel parking.

What's a stroad?

A stroad is the futon of traffic devices. A futon is a bad, uncomfortable couch that converts into a bad, uncomfortable bed. It tries to do two things, and does both of them poorly. A stroad can’t decide if it’s a street or a road. Because it combines high speeds with lots of complexity and randomness, it’s a great place to go if you want to be involved in a wreck. Otherwise, best avoided, especially on foot/bike.

A street, in Marohn’s taxonomy, is a platform for building wealth. Personally I dislike the financial focus, and like to think of it as a platform for building community as well. Think of the places you like to walk – you grab a coffee, walk down to the bookstore, grab a couple plants at the nursery, and if you’re lucky, walk or bike home. Cars are often allowed, but they are people-centric places. Traffic moves slowly and stops frequently. People are free and safe to walk and bike. That’s a street.

A road is a way of connecting places people want to be. Think of a highway or, as Marohn likes to suggest, a railroad. A road is not a place to do anything, other than get to where you want to be. Traffic enters and leaves via on-ramps; there are no pedestrians or bikes; speeds are high and driving is easy.

Read more about stroads at the Strong Towns website.

Okay – now I'll shut up about urbanism.

The Nickel Boys

by Colson Whithead

I loved this book so much I finished it, went back to the beginning and started over. Colson Whitehead is the brilliant author of The Underground Railroad, which I read a few years ago. I’ve wanted to read The Nickel Boys for years but did not get to it until now.

I loved this book so much I finished it, went back to the beginning and started over. Colson Whitehead is the brilliant author of The Underground Railroad, which I read a few years ago. I’ve wanted to read The Nickel Boys for years but did not get to it until now.

The novel is set mostly during the Civil Rights movement, and follows a Black boy named Elwood who is being raised by his grandmother in Tallahassee, Florida. Elwood is bookish and precocious, but ends up being sent to a prison-alternative “school” called the Nickel Academy for Boys after being falsely accused of stealing a car. Soon he discovers that the Academy is not all it claims to be. These are not really spoilers – the book opens with the discovery, years later, of a secret graveyard on the Nickel campus containing the remains of many students who the school had reported as runaways.

Like The Underground Railroad, this is a violent and challenging book. But it is masterfully written and compelling. Colson Whitehead was inspired to write the book after reading about the real-life Dozier School for Boys. The book is a fictional account based heavily on reporting about what happened at Dozier.

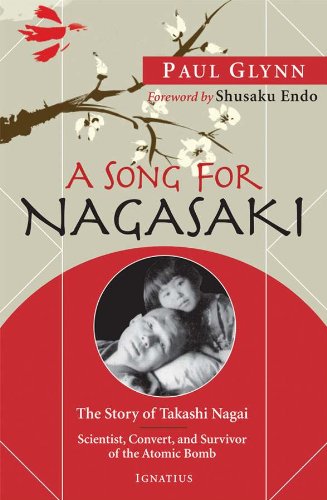

A Song for Nagasaki

by Paul Glynn

This biography of Takashi Nagai, the “saint of Urukami,” was another book I couldn’t read just once. I’ve gone back to it repeatedly in the last year, and given copies to several friends.

This biography of Takashi Nagai, the “saint of Urukami,” was another book I couldn’t read just once. I’ve gone back to it repeatedly in the last year, and given copies to several friends.

Takashi Nagai was a Japanese doctor, raised culturally Shinto but functionally an atheist, who encountered Catholicism through the writings of Blaise Pascal. After months of wrestling with Pascal’s thoughts, he decided to do an “experiment,” and went to live in a Christian household in Urukami, near the University of Nagasaki where he was studying. There he would meet his future wife, a devout Catholic named Midori who began praying for him. He was drafted into the Japanese Army during the occupation of Manchuria, where he saw first-hand how vicious people could be to one another, and how deeply the world needed love.

Years after his conversion and marriage, and already suffering from advanced leukemia, he survived the bombing of Nagasaki, while Midori was vaporized in their home. He devoted remaining few years of his life to studying the effects of radiation on the human body – something that he as a radiologist, a radiation poisoning victim, and a resident of one of the two cities to have a nuclear bomb dropped on it, was uniquely qualified to do. But he also wrote at length about Japan’s need to heal after the horrors of war, to seek forgiveness and to forgive their enemies.

Nagai was an incredible man, and Paul Glynn’s biography is excellent. Like Walkable City, if you buy this from a local bookstore and don’t like it, I’ll buy your copy off you for whatever you paid.

The Other Stuff

Movie: Citizen Jane

Sorry folks — we’re back to urbanism. This is a great documentary about Jane Jacobs and her war to save New York from Robert Moses. And you can watch it for free right here!