Le Corbusier’s influential vision of totalitarian architecture has never coexisted with organic human reality.

No single person — no elected official, designer, planner, architect or style-setter — has had a more profound effect on the built environment worldwide than the Swiss-French architect and city planner Le Corbusier. His buildings litter the covers of books and magazines on architecture. He fathered the concrete-based architectural movement of brutalism, and was one of the founders of architectural modernism; the “international style” of architecture is heavily indebted to him. But even more significantly, his ideas about cities have radically reshaped the places we live, especially those American cities built mostly after World War II. And yet most of us have never heard of him. While his many books and articles contain the musings of a visionary, they also provide alarming clues about why so many of the places we have built over the last hundred years are soul-crushing.

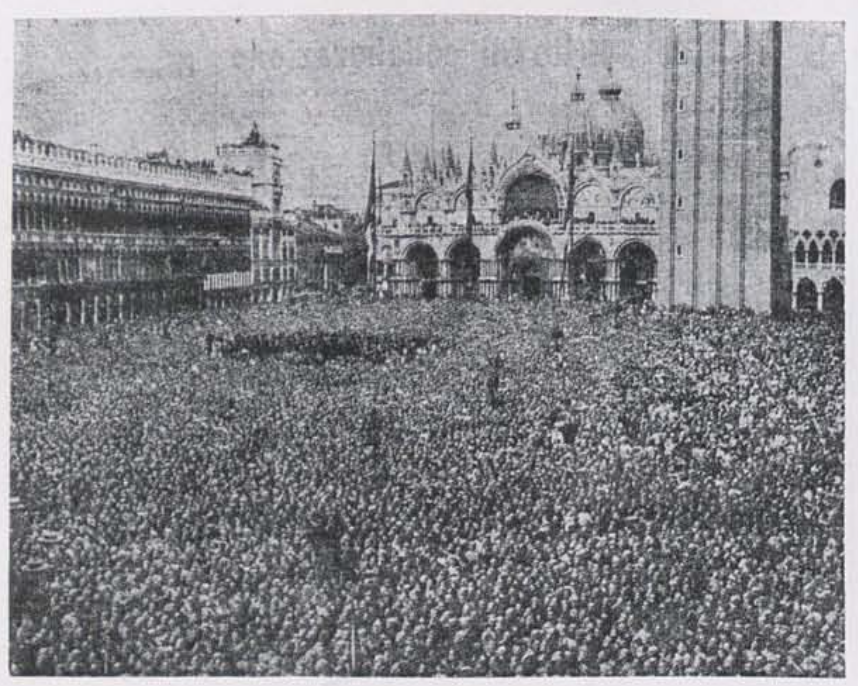

Le Corbusier’s Radiant City

When he published his seminal work, The Radiant City, in 1933, Le Corbusier was clear about the scope of his project. He was not just laying out some principles for the organization of modern cities, or providing solutions to the problems of industrialization. Rather, his purpose was “a manifestation of the new spirit of our age,” the creation of human happiness through modern technology, analysis, and planning.

Elsewhere, Le Corbusier had written that “there is a new spirit: it is a spirit of construction and synthesis guided by a clear conception… A GREAT EPOCH HAS BEGUN.” He would usher in this great epoch, in which cities were laid out following rational principles, where people could breathe freely, walk through green open spaces unmolested by vehicle traffic, and feel sunlight in their bedrooms and offices. He believed deeply in the power of human ingenuity, of data and calculations, and of rational design. His was a future based on the success of the American factory, the grain elevator, the automobile, and the steamship. These masterpieces of efficiency were his models for the reorganization of all of society, and he was anxious to begin this work.