When I started writing, I also started reading more. So I figured it would be natural enough to write periodically about what I’ve been reading. This turned out to happen a total of once in the last two years. Well, without further ado, here are a few of the best (and one which is by far the worst) books I’ve read in the last year. I decided to focus this volume on architecture and urbanism, because I’ve been reading a lot on the topic. But there’ll be another before long with a greater variety of books.

The Death and Life of Great American Cities

Jane Jacobs, 1961

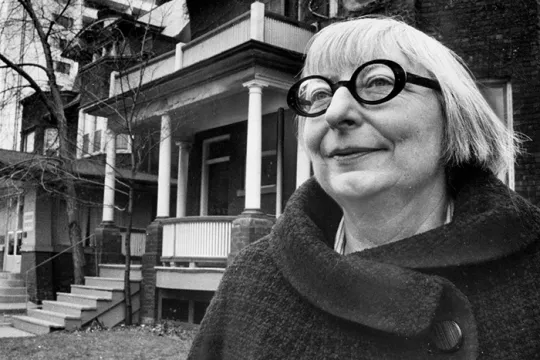

Jacobs is most famous for her idea of “eyes on the street.” Cities are fundamentally different from towns, she argues, because they must be places in which strangers are, and feel, safe. Her street in Greenwich Village is safe because there are eyes on it at all times – hers and those of her neighbors, the shop owners, bar patrons, school kids, and shoppers. Children play hop scotch in front of her flat, and run up and down the block, without the slightest fear. Meanwhile, parents on her street do not let their children play at the nearby park without being closely supervised, and for good reason. In the ideology of Robert Moses and his ilk, parks are the panacea of the city. Meanwhile, in actual 1961 New York, Jacobs writes, if you want to get murdered, she has several parks to recommend.

This book is a clear-eyed and realistic assessment of what allows cities to live and grow, and what kills them. If you love your city – and even more so if you loved your city and fear what it has become – you should read this book.

A Pattern Language

Christopher Alexander et al, 1977

Imagine the following experiences:

You walk into a living room of an unfamiliar house, and feel instantly at home. You hear yourself breathing more deeply. You feel comfortable.

You sit and sip coffee in a piazza in some European town, read your book, watch how the sun plays on the pavement, watch people walk by. Before you realize it, two hours have passed.

You walk into a room – a classroom, a courtroom, the DMV – and feel instantly uncomfortable. Your neck stiffens. You can’t wait to be somewhere else.

What makes these places affect you in the way they do? Is there something objective to it? Why do some places seem to give life, while others crush it? If you’re like me, you ask yourself these questions a lot. Christopher Alexander and his colleagues seek to illuminate these questions in A Pattern Language.

In A Pattern Language and The Timeless Way of Building, Alexander argues that there are patterns – common ways of addressing certain sets o problems and circumstances in cities, homes, and public spaces – that give life, and ones that destroy it. These patterns interact much like a language: they have a grammar; certain patterns combine with others to make coherent spaces. The discovery of these patterns is not rocket science, but it takes careful observation. Alexander and his colleagues provide 253 such patterns that they believes give life in A Pattern Language. For example, in “Six-Foot Balcony,” they argue that there are essentially two kinds of balconies in the world: ones people use, and ones they don’t use. All balconies people use (for things other than bike and grill storage) are at least six feet deep, providing space to sit around a table with people, and most are partly recessed into a building, providing shelter from wind and a sense of safety. Look at the balconies around where you live with this in mind, and see if it’s wrong.

This is one of the most read, and I think most misunderstood books, in architecture. Many contemporary architects hate it, in part because Alexander seems to hate them, along with most other “experts.” There is a sympathy here with Wendell Berry – a suspicion of the need for an expert to design our lives and cities (and diets and farms) for us.

I would note that this book has a lot of limitations. Alexander is prone to pontification, and rarely acknowledges when he is in dialogue with others. In these works he seems to think of himself as semi-divinely inspired oracle. In A Pattern Language he had the great benefit of collaborators and editors. In some of his other works (especially The Timeless Way), he could really have used them.

Towards a New Architecture

Le Corbusier, 1923

Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, better-known by his adopted name, Le Corbusier, is the most influential architect of the 20th century by almost any measure. This is the case more because of his writings that because of his buildings. One of his most widely read books is the 1923 Towards a New Architecture. Anyone interested in understanding the story of modern architecture should read it.

I will now stop trying to write an objective review of this book. It is one of the strangest and worst books I’ve ever read. If it belongs in the “canon” of modern texts, and I think it does, it belongs in the intersection of the Venn Diagram containing works of dystopian fiction on the one hand, and works of ideological propaganda masquerading as philosophy on the other. Think 1984 and Brave New World meet Mein Kampf and the Communist Manifesto. Le Corbusier is convinced that modern means of production have made most of the past obsolete, and that the “new spirit of man” is immanent. He holds tradition in contempt, except in as much as it lines up with his ideology, which centers on the use of primary geometry (lines, rectangles, spheres) and machine-age technology.

Le Corbusier points to the factory and the grain silo as examples of the “new architecture” bursting forth from the minds not of architects but of engineers. From here he sees a new and glorious future, the coming of a “new spirit. ” Here is a brief excerpt:

A house is a machine for living in. […]

A great epoch has begun.

There exists a new spirit. […]

We must create the mass-production spirit.

The spirit of constructing mass-production houses.

The spirit of living in mass-production houses.

The spirit of conceiving mass-production houses.

If we eliminate from our hearts and minds all dead concepts in regard to the house, and look at the question from a critical and objective point of view, we shall arrive at the “House-Machine,” the mass-production house, healthy (and morally so too) and beautiful in the same way that the working tools and instruments which accompany our existence are beautiful.

Welcome to the most soul-crushing of suburbs. Except that Le Corbusier actually wanted to build mega-cities, fully planned, where all housing would be contained in “towers in the park” surrounded by acres and acres of trees and grass. His monstrous designs might never have been inflicted on the world had it not been for people like Robert Moses.

Given all this, Le Corbusier’s clientele should come as no surprise: he built buildings for Stalin; he cozied up to Mussolini and tried to influence Italian fascist architecture; and he sought to become the Nazi-collaborating Vichy regime’s urban planning guru. “Little by little,” Le Corbusier wrote in 1935, “the world is moving to its destined goal. In Moscow, in Rome, in Berlin, in the USA, vast crowds are collecting round a strong idea.” This caption accompanied a photo of a fascist rally in Venice. His worldview required totalitarianism (as Theodore Dalrymple argues powerfully in his article in City Journal). It needed to be imposed on people. It contained no space for politics, for individual people and communities to have any degree of self-determination outside their homes. His aspirations of joining an actual totalitarian regime went nowhere. Fortunately for him, though (and unfortunately for the entire rest of humanity) he found acolytes such as Robert Moses who could impose his ideas on cities around the world. His ideas, both his brutalist architecture and his totalitarian urban planning, made it into the mainstream, to the point that it is now impossible to point to specific instances of his influence. Everything from suburban (mass-production) housing and strip malls to parking garages and high rises owe something to Le Corbusier.

If you wonder what happened to architecture – why much of the built world of the last century is so distinctively ugly and antihuman – you should read this book. And then you should read Jane Jacobs and Christopher Alexander (and Wendell Berry and…) and regain some hope for humanity.

Well, that’s it for this installment. You might not be surprised, if you made it this far, to learn that I’m working on a few pieces of writing about architecture. Stay tuned on that front!

Love it! Thanks.